On a normal midweek morning at dawn, Bureh Beach would look more or less as it has since time immemorial. The ochre-yellow sand would be totally deserted, save a couple of sand-speckled, mongrel puppies playfighting in the lagoon. The intensifying sun would project shimmering highlights on the deep metallic-blue ocean, from the steep waves clawing at the shore to the horizon. The calm would stretch from the surf to the surrounding thick mangrove forest, which leads down to the Banana Islands, shrouded in the humidity trapped there by the trees.

But today, a hazy early-December morning, a flurry of activity is taking place. Around 30 young men – and one woman – are performing warm-up stretches in board shorts on the pillowy sand, fixing determined eyes on the ferociously building waves. Sierra Leone’s first national surf championship is taking place – two years after it became the 98th member nation of the International Surf Association (ISA) – and each competitor is preparing to battle it out to qualify as the country’s official surf representative. With enough training, the winners could ride that wave all the way to the 2020 Olympic Games, where surfing will feature for the first time.

An hour and a half south of Freetown and next to the 300 people-strong Bureh Town, Bureh Beach is home to Sierra Leone’s first and only surf club. Made up of a bright blue-painted club house and five modest huts providing basic accommodation, the small complex was hand-built by a group of 15 local young men, with materials gathered from the surrounding bush. Equipped with a collection of 15 battered, second-hand shortboards – the only boards in the country – the group today offers Sierra Leone’s only surf lessons (five of them having recently completed the official ISA level 1 surf instructor course). As well as bringing surfing to a country unfamiliar with the sport, the group is creating a 100%-sustainable, eco-tourism offering for visiting travellers – and with that, attracting a new kind of attention to a country that’s been dealt unfavourable international coverage for far too long.

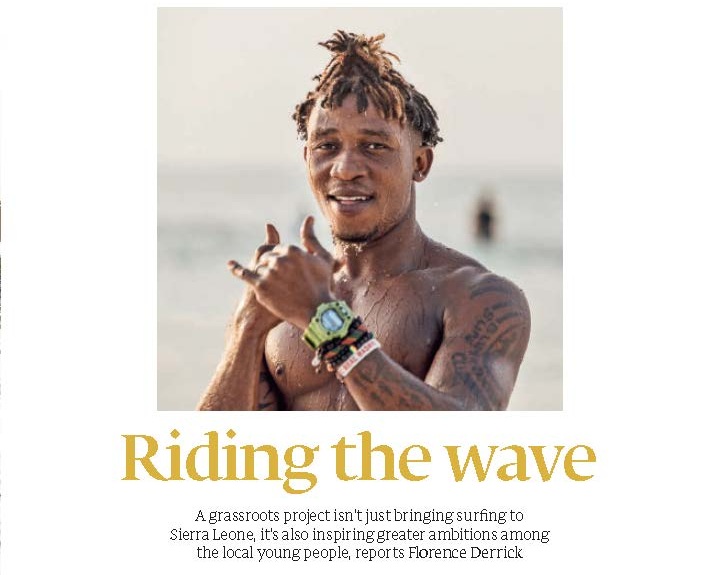

It all started 14 years ago, when a 10-year-old boy called John Small, from Bureh Town, met an American expat called Dave. “He used to come here every weekend to surf,” the now-24-year-old Small tells me, sitting on the sand beneath the shade of a palm leaf-woven parasol. Mid-competition, he’s just jumped out of the water and his short, half-bleached dreadlocks flick seawater over his salt-dusted shoulders. “Every weekend I’d borrow his board and paddle-paddle, struggle-struggle until I started to get my balance. One day I stood up and caught a wave.”

After a year, Dave left – and gave Small his surfboard as a parting gift. The 11-year-old continued to teach himself to surf, passing on his new-found knowledge to his local group of friends, who turned out to be just as resourceful as he was. “I started surfing when I was seven,” says 22-year-old Charles Samba. “Back then it was hard. There was only one surfboard – in the whole country! We were learning to surf on bodyboards as kids. But more visitors started to surf at Bureh Beach, and we’d make friends with them and they’d leave their boards behind.”

One day in 2010, Irish NGO-worker and amateur surfer Shane O’Connor arrived in Bureh, on a weekend trip from his base in Freetown. He saw potential in the young group of surfers and launched a fundraising campaign to provide money for equipment and the building of the club house. It attracted the attention of German international aid organisation Welthungerhilfe (WHH), who donated funds and recruited Austrian Stefan Pfeiller to manage the newly built club. Pfeiller had managed surf clubs in France and Morocco, and has travelled between Bureh and his home at every opportunity over the past four years to support the club, developing a sustainable management structure and business model, and linking it up to the ISA.

“For guys like this in Sierra Leone, it’s somewhere between hard and impossible to find a proper job,” Pfeiller explains in between surf sets. He’s here to judge today’s championships, appraising each surfer’s tight turn and cutback from his vantage point on a smooth, large rock, noting down scores in pencil and cheering each competitor on with equal enthusiasm.

“There’s not much work in tourism,” he says. “There’s fishing, but big sea trawlers are taking coastal fishing jobs away. The only other option is to move to Freetown to do terrible work, for terrible pay – selling stuff on the street or mining.”

For Pfeiller, this is what makes Bureh Beach Surf Club so special. It’s creating meaningful, sustainable work for young people otherwise lacking in opportunities. “To get to live the life of a surfer, to be free and spend every day in the water? It’s everything to them,” he smiles broadly. “The club is their life – they even take it in turns sleeping here. It runs totally independently and sustainably. They’re so proud of it and it’s amazing to see how professional and passionate they are.”

But it’s not been an easy journey for the club or the boys that have made it their life. When the Ebola virus hit Sierra Leone in 2014, it thankfully didn’t reach Bureh – thanks to the diligence of the community – but it had a severe impact on the surf club’s development. “There were times when no one would come to Bureh for months, and when the quarantine zone was up, it wasn’t even possible to leave to get food,” Pfeiller recalls. “But everybody from the project kept it up.”

For one particular surfer, Kadiatu Kamara, there’s been another, unique set of challenges. ‘KK’ is the club’s first and only female member, and to date, the only woman in Sierra Leone to have ever surfed a wave. “When I started surfing, it wasn’t easy. I was scared of the waves, scared of the board, scared of sharks,” she reveals. “I didn’t know how to swim. The boys made fun of me when I fell in the water, and sometimes they’d even take my board away so I’d have to learn to swim. They taught me everything, though.” It was thanks to the surfer boys that KK stuck it out, when a bad experience in the water almost ended her surfing career before it even began.

“One of the first times I ever went in the water, my leash got loose from my foot and I lost my board,” she remembers solemnly. “I couldn’t swim. Some of the boys saw me and pulled me out of the water. I’d swallowed plenty of water, they had to get it out of my lungs.” Scared of what would happen to her family without her there to support them, Kamara vowed to quit surfing for good.

But for a month, Small, Samba and their friends would visit and urge her to rejoin, keen to encourage other girls in the town to surf and with promises that one day she’d make a living from the sport and club. They successfully persuaded her – and she’s now Sierra Leone’s only, women’s national surf competitor.

KK is a force to be reckoned with. Having faced derision from the local community – “it’s hard to encourage girls to surf. Their mums are scared of the water and don’t let them go near it. Because of that, they make fun of me and say I am wasting my time” – she displays a level of determination and dexterity that runs even deeper than that of her male counterparts. For Kamara, surfing means escapism – both from daily concerns, and in terms of her future plans to surf in international competitions. “When I go in the water, I’m so happy,” she says. “I learn things. I feel different in my life – sometimes like I’m surfing in a different country. I wish that I will do that one day.”

If Pfeiller has anything to do with it, she will – along with Samba, who, by the end of the day, has won first prize in the ISA men’s championship. “Our biggest dream is to one day attend the Olympic Games,” Pfeiller enthuses. “I feel like we’re going to get there because the surfing level here is really, really high, especially when you think that all the boards here are more or less broken and these guys have never had a proper surf lesson. We’ve got seven-year-old kids doing turns on bodyboards, which is so amazing.”

For the surfers of Bureh Beach who are pursuing their own careers, it means far more than personal gain. As it grows – funded increasingly by travellers visiting for surf lessons and a rustic stay on the beach, rather than donations – the club is investing in scholarships for local children, helping to pay their school fees while providing surf lessons followed by hot meals. For KK, any success she enjoys will encourage girls to join her in the water. As for Small, his dream is to change the external perceptions people have of Sierra Leone and present it as a professional surfing destination.

“My ambition is to put Sierra Leone on the map, so people will know that surfing is happening here,” he says, proudly overlooking his fellow surfers who are sitting cross-legged on the sand and cracking open a post-contest lager. “We just want people to know what it’s really like here and to have the confidence to come.” sierraleonesurfing.com