Willie Tucker is fluent in chimp speak. From the high concrete look-out platform, separated from an eight-acre enclosure by a tall mesh fence, he howls and hoots into the leafy rainforest that stretches out before us, blending into hazy green-blue mountains as it hits the horizon. For a few moments, the only sound disturbing the secluded landscape is the siren of cicadas – as loud as a car alarm, and a constant companion in the Sierra Leone bush. Then, a slight but unmistakable rustle in a distant treetop signals a response. One by one, a group of 15 chimpanzees emerges from the undergrowth, swinging languidly between branches and shimmying down tree trunks until they’re crouched on the red-brown earth just metres in front of us. “Tito,” Tucker calls out to the pack’s 30-year-old alpha male, whose fuzzy hair ruffles out from his back like a brush. “How are you today?”

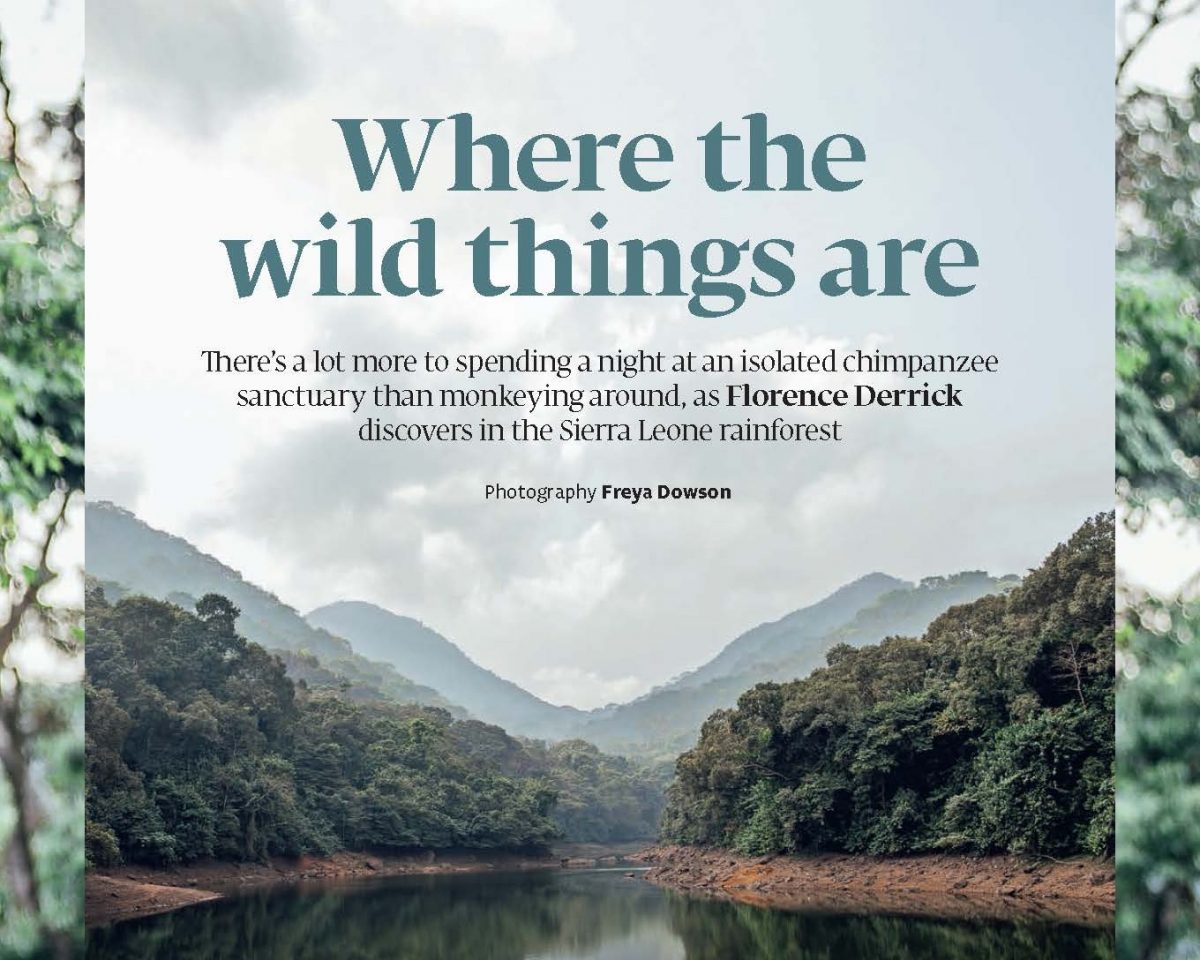

It’s dusk at Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary, in the Western Area Peninsula National Park just outside of Freetown, and the 76 chimps that call it home are hungry. On one of two daily tours of the sanctuary, I watch as handlers toss the primates their dinner – cricket ball-sized globes of local bulgur wheat, grains and beans – before coaxing them into their dens for the night. Visitors that make the hour’s drive from the congested capital city to the 100-acre refuge – which culminates in a bumpy 4×4 ride up a steep dirt track pitted with potholes – come to take a peek at Africa’s most endangered species, and a breather from the capital’s frenetic energy. For not only is Tacugama Sierra Leone’s leading wildlife conservation centre, it’s also its primary eco-tourism offering: beyond the sanctuary gates are six eco-lodges half-hidden in dense, vibrant-green jungle.

The isolated setting, strung with hammocks and abuzz with tropical birds and butterflies, feels like paradise – which should come as no surprise. The Tacugama site is a precious pocket of preserved land in a country caught up in a spiral of poorly controlled deforestation, mineral exploitation and slash-and-burn agriculture. At the beginning of the 20th century, 70% of the country was covered in thick forest. Today, Sierra Leone’s total forest coverage is a meagre 4%. Not only does this present grave risks to its population – last August’s devastating landslide in Regent, just 2km from Tacugama, was fundamentally caused by over-deforestation in the surrounding hills – it also contributes to the mass habitat loss of wild apes. Add to that the illegal trading of chimpanzees as novelty pets and the ongoing scourge of hunting them for bushmeat, and it’s no wonder that the native chimp population currently stands at just 5,500.

“Chimps are no longer safe in the wild,” says Tacugama’s founder Bala Amarasekaran. “We set up this sanctuary to rescue orphaned and endangered chimpanzees, but we’re increasingly focusing on the root of the problem: that Sierra Leone has very few patches of suitable habitat for chimps left.”

Tacugama’s work has expanded into a countrywide conservation project – but it all began with a chimpanzee named Bruno. Twenty-four years ago, a newly married Amarasekaran and his wife were travelling in the rural ‘upcountry’ when they came across a severely malnourished baby chimp tied to a tree. Unable to walk away, they bought him for $20 (€17). “We nursed him back to health and he became a child to us,” smiles Amarasekaran. The experience alerted him to the cruel, widespread practise of keeping baby chimps as pets until they become strong enough to challenge their owners (adult chimpanzees are five times stronger than the average man) – often leading to them being abandoned, or killed. Amarasekaran gave up his career in accountancy and set up the sanctuary in 1995, with a government mandate, EU funding and Bruno as its first resident.

Today, Tacugama’s primary mission is to confiscate chimps from those illegally keeping them (mostly expats, according to Amarasekaran), and rehabilitate the apes before re-releasing them into the wild. However, the primates arrive at the sanctuary in varying physical and psychological states. “Some don’t even know how to climb a tree,” says sanctuary supervisor Tucker, who’s been Amarasekaran’s right-hand man since day one. Once they’ve completed a 90-day quarantine period and a series of medical check-ups, the chimps are gradually taught how to climb, build nests, and socialise, being slowly introduced to groups of other chimpanzees.

In the wild, chimpanzees live to an average age of 50 in groups of around 50, and the sanctuary aims to replicate their natural life cycle as closely as possible. The youngest chimps spend their days in a modest-sized enclosure, cheekily leaping between poles and ropes, ambushing each other and hurling toys towards unsuspecting passers-by.

Over the course of their lives, they’ll gradually progress to the final-stage enclosure – where Tito’s group lives – which is big enough for them to explore, build nests and forage for food. Though there’s an ongoing low-level search for a suitable site for the chimps’ eventual release, the continual loss of habitat in Sierra Leone makes it unlikely that these chimps will ever be able to live in the wild here again.

“We think of these 76 chimps as ambassadors for those in the wild,” says Amarasekaran. “About 1,000 local kids come to our sanctuary every year to learn about chimps. When people actually see them, they begin to understand and respect them more.” That’s where the rest of the sanctuary’s work begins: with community outreach programmes that engage the public through education and sensitisation activities.

Having met the chimps (from a safe distance, as human contact with the sometimes-aggressive primates is strictly forbidden) and dined on homemade, creamy groundnut stew, I head to my lodge for the night, which offers a comfortable but no-frills jungle-living experience. As is standard in much of Sierra Leone’s accommodation, Wi-Fi is non-existent, electricity is only generated for a few hours each day and the water comes out of the taps stone cold. As the orange sunset sinks into inky darkness and the cicadas’ calls reach near-deafening decibels, I tuck a mosquito net around my bed and settle in for a night’s sleep punctuated by the scratches and rustles of nearby bushbabies and the distant screeching of chimpanzees.

It’s sunrise the next morning and ex-army sanctuary patroller Emmanuel Williams is tucking a machete into the polished leather belt of his immaculately pressed, navy trousers. “We engage in intensive patrolling to prevent deforestation and poaching,” he states, wielding the blade to clear a path as we enter the thick bush, on one of six guided hiking trails offered by the sanctuary. “We stop poachers, sensitise them and explain the disadvantages of killing wildlife. If they persist, we have the mandate to take them to the police station.”

A former radio communications corporal, Williams applies military precision to every aspect of safeguarding Tacugama and its surrounding territory, as well as his approach to leading guests on bush walks. Though cobras, crocodiles and all manner of poisonous spiders live in the rainforest, on most treks guests only encounter a vibrant kaleidoscope of butterflies and tropical birds, and ant trails so thick they look like vibrating black tree roots.

I pick my way through the undergrowth, following Williams closely as he beats back the long spiky grass blades snatching at my clothing, and inspects the forest carpet of sand, leaves and twigs for evidence of wild animals, invisible to the untrained eye. Mid-scramble up a chalky, rocky slope – sweat prickling as the day’s hot humidity begins to set in – he halts and picks up a round, green fruit casing, cracked open like a conker to reveal a silky white interior. “Bush berries,” he murmurs. “A vervet monkey ate this. It’s fresh – they’re nearby.”

Over the course of the three-hour hike, we pass termite hills towering two metres above the ground, a waterfall plunging fresh water towards Freetown, and the Congo Dam – a sea-green lake obscured in the forest’s depths, and one of the capital’s main water sources. When the midday sun drives me reluctantly back to my lodge, I find a homemade lunch laid out under a shaded canopy of trees: whole grilled fish, cassava wedges, spiced couscous and a devilishly oily tomato and vegetable stew.

Tacugama has set itself a goal to be 100% self-sufficient by 2020, and its growing tourism program is a big part of the plan. In addition to the hiking trails, the sanctuary offers occasional yoga retreats on a serene, open-air platform in the heart of the rainforest, and half-day bird-watching tours, which begin at dawn with a breakfast of eggs, coffee and fresh fruit. Going forward, the team plans to create a brand-new information centre and spa, plus host cookery classes, events and concerts – as well as ensure that each lodge has hot water and plug sockets (currently in very short supply).

Though ambitious, each of these endeavours will require employing people from the local community – another core part of the Tacugama philosophy, whose outreach work proves that conservation is just as crucial for protecting people as it is for animals.

“We’re not just here for chimps,” insists Amarasekaran. “Sierra Leone is a poor country and when people are hungry, it’s difficult for them to practise conservation. We’re working with 44 communities and providing them with economic alternatives that don’t lead to human-chimp conflict: growing crops that chimps don’t eat, like cassava, ground nut and rice, or giving farmers fertiliser so they don’t slash and burn.”

As I climb into the beaten-up 4×4 that’ll take me back to Freetown, I reflect on the unique history of Sierra Leone that’s left its people and its chimps with such complex challenges. Yet the Tacugama sanctuary has managed to safeguard its family – human and chimpanzee – from both civil war and the 2014 Ebola outbreak, and it’s clear that Amarasekaran’s dedication is only growing stronger as years go by. “For me, Tacugama is not a sanctuary – it’s a movement,” he concludes. “However hard things get, I don’t see this as work. I’ve made a promise to take care of these chimps for the rest of their lives. That’s the deal.” tacugama.com