It’s 7am when my bleary-eyed hotel breakfast of ham, bread and cheese is interrupted by an unexpected din. A wall of cuckoo clocks above me bursts into song, teeny wooden birds poking their heads into the dining room and chirping their morning wake-up call in chaotic discord.

I’m in Freiburg im Breisgau, a small and eco-minded university city in the heart of Germany’s Black Forest. The south-westerly region – bounded by the Rhine valley to the west and south – is renowned for its mountainous scenery, its namesake chocolate gateau cake and its cuckoo clocks, which were invented here in 1730. Or possibly not.

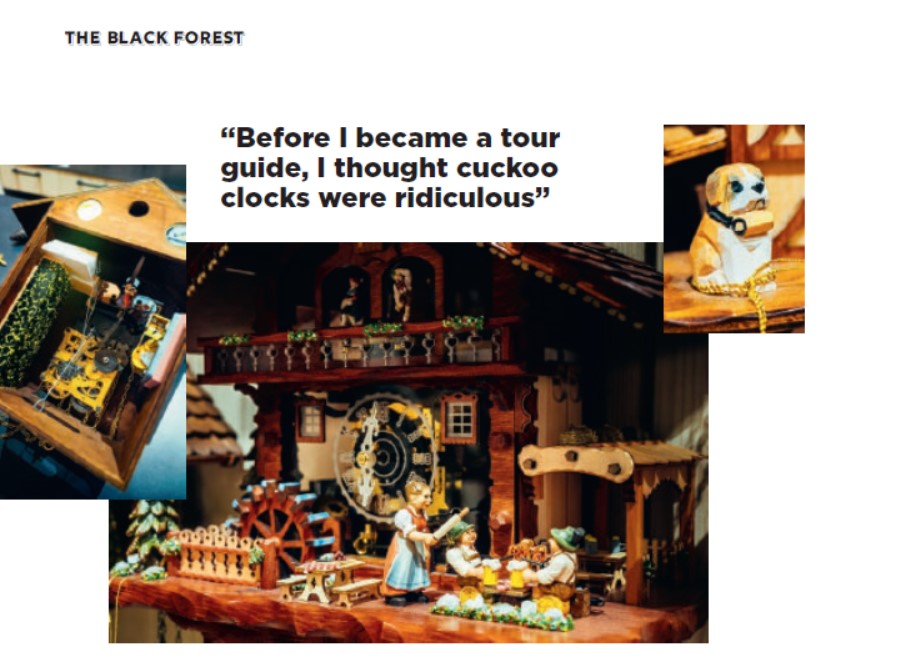

As it happens, similar musical timepieces were produced back in the 1600s in Bavaria and modern-day Poland, and rivals found in Switzerland and Austria. Yet it was the craftsmen of the Black Forest who built an empire on cuckoo clocks in the 19th century, with some 3,000 clockmakers reportedly producing 40 million of them between 1820 and 1840. The industry is still a big money-spinner today, with factories producing tens of thousands of clocks a year to be sold to American and Asian tourists for up to €23,000. And it’s not the only selling point of the Black Forest that’s built on myth and legend.

A 40-minute drive from Freiburg in Hinterzarten is the Schwarzwälder Skimuseum, where the claim that skiing originated in the Black Forest Highlands in the 1890s is made into an exhibition. There is plenty of evidence, though, to suggest that people were strapping wooden slats to their feet in Scandinavia centuries earlier.

Even the famous Black Forest Cake, oozing with cherry schnapps and lashings of whipped cream, was reportedly invented in Bonn, a four-hour drive north. And the Brothers Grimm, Germany’s most celebrated storytellers, are said to have been inspired by the region’s thick woodland when they wrote Hansel and Gretel – despite the fact that they lived exclusively in the northern half of the country.

But like countless others before me, the mythology of the region has drawn me in. I’m here on a road trip (forget about public transport in this part of the world) to find out why this folkloric setting has captured so many imaginations – and to find out if it can capture mine.

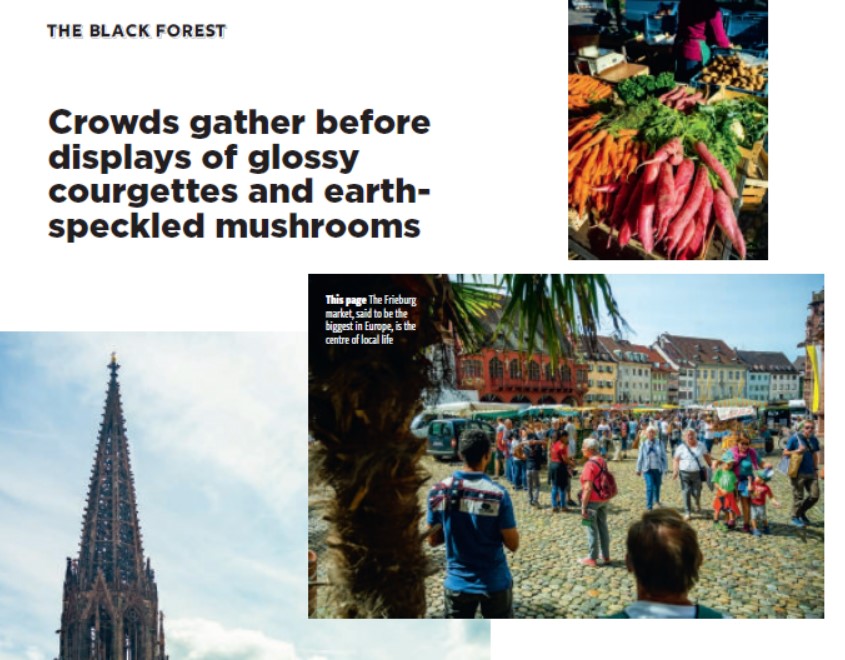

“The Black Forest begins inside Freiburg,” my guide Simone Brixel tells me as we climb into her black SUV. It’s true: even downtown, in the shadow of the Gothic Minster’s red-brown spire, the dark woodland encroaches. It rises on thicketed hills surrounding the city’s natural basin, and creeps into its suburbs. It’s present in the weekday market – rumoured, in typical Black Forest style, to be Europe’s biggest, bringing 160 farmers to Freiburg’s town square. In between wurst stands and hipster tofu counters, grandmothers clutching shopping lists elbow past groups of dreadlocked students to browse punnets of forest raspberries blushing in the sunshine next to glossy rows of courgettes and earth-sprinkled mushrooms, all gleaned from the surrounding hills. Despite (or perhaps because of) Freiburg’s hip, progressive identity, the wilderness is never far away, and we’re about to drive deep into it.

Brixel is a Freiburg native who spent 18 frenetic years working a burn-out, high tech job in Silicon Valley. But seven years ago, the calm of the forest called her home. She launched Black Forest Tours, one of the area’s first English-speaking driving tour companies, which has seen growing success as more international travellers come to the area each year.

“It was the last place I thought I’d end up, after pursuing such a fast-paced life,” she confesses as we turn onto the highway. “But it’s a really laid-back area. We like eating and drinking, hiking, cycling. We make wine, we have Michelin-starred restaurants This is where you really see Germany, because it’s where Germans come on holiday. It’s for the advanced traveller in that way.”

As we wind along hill-hugging roads and tunnels cut into the rocks, we pass mountain bikers wobbling with the effort of their climb and enormous, 400-year-old farmhouses, still lodging cattle on the ground floor, with families under the tiled roof above. Brixel explains that farming drives the region’s economy today. Supposedly Germany’s sunniest region, and among its most remote and verdant, the Black Forest is primed for growing anything and everything. It’s particularly good at producing the kinds of red fruits that end up in a Black Forest cake – something I’m eager to try.

But it’s still early, and the cool, misty air that enshrouds the approaching mountains makes me wonder whether the area’s reputation for sunshine is just another myth. We drive for an hour, pausing at the Todtnauer waterfall to marvel at the river tumbling from 97 metres high, before arriving at Bernau, a hamlet on the edge of the Zauberwald (which translates as ‘Magic Forest’). Under a light mist of rain, we begin a walking trail that winds through random sculptures of wizards, polka dot mushrooms and woodland creatures. Though wolves are reported to have made a comeback in the region, we see none of the big bad variety – just a wood-carved specimen among the undergrowth. The trail is almost empty, and silent save for the soft sounds of brooks and birdsong. Its broadleaf trees are vivid green, while the rocks that line the path and streams are coated in soft moss. It’s a magical environment, even without wicked witches and porridge-eating bears.

The trail takes an hour and we emerge from the woods to spot sunshine struggling through the clouds. Keen to catch it, we head north to Lake Titisee – another 30-minute drive – and the region’s most famous holiday destination. “It hasn’t changed since I came here as a little girl in the ’80s,” says Brixel as we park up between number plates from all over Europe. Packs of tourists follow guides waving flags, children munch on pretzels clutched in paper bags, street stalls flog lederhosen-printed T-shirts. A creaking Ferris wheel adds a bit of old-school charm to the setting.

“In the morning, this is a locals’ lake,” Brixel tells me, as we watch the half-hourly boat cruise pitch off from the shore, packed with anoraks in every prime colour. “You just have to get here before the buses arrive. But to go where the locals really go, Lake Schluchsee is 15 minutes down the road. It’s got little beaches, grass verges for barbecues, swimming, boating.” Almost completely empty, it’s a stark contrast from the lederhosen and clock shops – but a visit here requires a bit of pre-planning. Without a picnic basket or a blanket, we decide to drive past and venture back into the wild.

But first, I insist on eating a Black Forest cake – and Brixel knows where to do it. A 10-minute drive away is For Gscheiten Beck, a pastry shop and distillery that’s been run by the Bizenburger family since 1977. Seventy-five-year-old Erich Bizenburger has been distilling schnapps – the fruit-based liqueur that’s been made here for 3,000 years – since he was 13 years old. When we arrive, he is presiding over a copper still of kirsch in-the-making. He beckons us over to peer into the hot still, where a cauldron of thick black liquid bubbles and swirls like lava. “Black Forest cherries,” he says with a twinkle.

Next door, Erich’s daughter Ramona is beginning a cake-making demonstration before a few dozen tourists barely able to hold back from drooling. Like Brixel (and many other locals) she’d left the region when she was young and worked all over the world, before returning to the forest a decade later to look after the family business. “When I was 17, this was the worst place in the world to live,” Ramona says with a laugh. “There were no bars, you had to drive everywhere. But I think you have to leave and see other places to understand the value of where you’re from.”

As her kids peek around the corner in the hope of being given a spoon to lick, Ramona expertly layers day-old, kirsch-soaked chocolate sponge with cherry jam and thick whipped cream. She shaves dark chocolate over the top and adorns it with fresh cherries. I dig into the thick slice she’s just cut. It’s surprisingly alcoholic, rich with fruit and as dark as the woods – the Black Forest on a fork.

Before we head back to Freiburg, we need to make one last stop, at Hofgut Sternen – a medieval horse station that’s been transformed into a recreation of a traditional village, which houses the Black Forest’s biggest complex of cuckoo clock shops. A multitude of shops are stacked wall-to-ceiling with the wooden clocks, in shades that range from golden beige to mahogany, and it’s an assault on the senses when they all go off in almost-unison. And there’s more to the clocks’ mechanism than a little wooden cuckoo. Dioramas depict old-fashioned regional scenes, from the ‘dumpling eater’ who shovels dumplings into his mouth in a robotic motion to the many, many depictions of housewives beating their husbands over a head with a rolling pin. They’re undeniably kitsch, but intricately carved and painted. “Before I became a tour guide, I thought cuckoo clocks were ridiculous,” admits Brixel. “But I have so much respect for them now that I know how much work goes into them.”

The craftsmanship on display is impressive, but what many clock-buyers don’t know is that the Black Forest’s most beautiful walking trail begins under a stone viaduct that borders the set of buildings. The steep, rocky track through some of the densest woodland around makes the Magic Forest feel entry level in comparison.

We set off through the dappled sunshine, the air scented with damp pine needles and earthy moss. Following the banks of a trickling stream, we soon become engulfed by tall beech tree trunks and thicket. Heavy beads of water weigh down leaves; branches are sticky with sap. Fresh blueberries burst on touch and ooze blood-red juice. We pick our way between slippery rocks and ferns until a wooden hut emerges through the branches. It’s an old mill, with water still pouring through its rusted wheels – but I’ve found my Hansel and Gretel moment. The secluded forest feels enchanted, even if a roaring tourist trade is taking place just a couple of kilometres away.

That’s the Black Forest’s charm, I decide as we climb into the SUV one last time. Origin stories are just the beginning of the plot. Whether it’s cuckoo clocks, cakes, the kind of pure-distilled kirsch that puts hairs on your chest or the forests whose thickets inspired creepy bedtime tales, there’s a reason why people always come back here to be bewitched by the region’s legends. Because they’re told better nowhere else. the-black-forest.com

Fine dining in the Black Forest

Baierbronn, a tiny town two hours north of Freiburg, has become not only the Black Forest’s culinary capital, but unexpectedly, Germany’s. It boats a collective eight Michelin stars at its top three restaurants and is well worth a stop-off on your own regional road trip.

For old-school decadence: Schwarzwaldstube

The gourmet restaurant of the 200-year-old Hotel Traube Tonbach opened in 1977 and has held three Michelin stars for over 25 years. Chef Harald Wohlfahrt presides over a menu of light, delicate dishes that celebrate the forest – think wild hare with cranberries and trumpet mushrooms. traube-tonbach.de

For an intimate date: Bareiss

Hidden in the pines is Hotel Bareiss, whose restaurant holds three Michelin stars thanks to its tiny eight-table dining space and dextrous menu that pairs beef, venison and fish from an onsite farm with vegetables and herbs foraged from the surrounding woods. bareiss.com

For an aromatic experience: Schlossberg

Claiming two Michelin stars, the latest restaurant to be awarded offers a 12-course menu based entirely around aromas: wild thyme, fresh-picked berries and earthy mushrooms drive the sensory experience, spiked with hints of rose and pine. hotel-sackmann.de